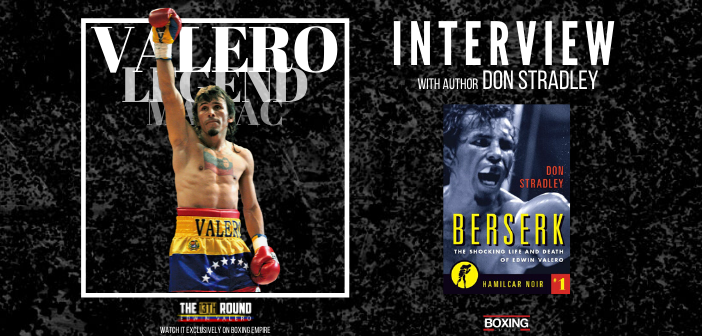

Edwin Valero played both hero and villain in his own Greek tragedy. Even now, nearly a decade after his shocking death, fans and haters still talk about “El Inca” in mythical terms.

That is why we chose the Venezuelan anti-hero as the subject of our first short documentary series, The 13th Round: Edwin Valero, which you can watch below.

We enlisted Don Stradley, author of the just-released, Berserk: The Shocking life and Death of Edwin Valero, to help guide us through this triumphant and ultimately tragic story.

Boxing Empire: Of all the boxers to write a book on, why Edwin Valero?

Don Stradley: Well, my publisher, Hamilcar (Publications) presented me with a bunch of names to pick from. I saw his name (Valero) and I thought he’d be a fantastic subject because he’s controversial. There’s a lot of different layers. It’s not just another boxing story. It’s a tragedy. It’s a murder. I thought I could do something interesting with it.

We know how the story ends, but let’s go back to the beginning. How did he get into boxing?

Boxing was very big in Venezuela. For a lot of young men from poor environments, it was a way out. He loved boxing. He didn’t want to just be the top guy in Venezuela. He wanted to be worldwide.

How would you describe him as a fighter?

He was an excellent boxer. He had two styles. There was a style he used in the gymnasium when he was sparring. And, there was a different style that he used in the ring when he was getting paid. He was really spectacular in a gym setting. He was very precise with his movements and perfect with his delivery. He was slick. He could get around on his feet. But once the bell rang for an official fight, he just went out swinging for the knockout. That was his reputation as a knockout puncher. He liked to give the people what they wanted.

People still talk about his ungodly power.

His power was unusual for a lightweight. I spoke to people who said he was so strong that he would actually make sparring partners cry. Grown men wearing helmets and padded gloves didn’t want to get in the ring with him so his trainers would find junior middleweights to spar with.

Fans still fantasize about a ‘Valero vs Pacquiao’ dream fight. How do you compare the two?

Pacquiao was a little quicker on his feet and with his hands than Valero. I would give Valero credit for being so smooth for a southpaw. He looked like a right-handed fighter, but he was fighting from the left side. Of course, we never got to see how far he was going to advance. But some people think he could have been as great as Manny.

Was the 2001 motorcycle accident the beginning of the end?

It was a big obstacle. It created a lot of delays in his career. He was going to sign with Golden Boy (Promotions) and they do the scan on his brain and they see that he wasn’t totally healed. He could get a license in other parts of the world. But in the United States, it was very difficult for him to get a license.

Did the crash play a role in his mental problems?

No one I spoke with felt that way. Everyone said that he was fine until the last year or so of his life. Not signing with Golden Boy was a big disappointment but I think it also, in a way, motivated him.

Ironically, it led him to become an international star.

Yeah, he really found himself in Japan. The promoters loved him. The fans loved him. The media loved him. They thought he was a rock star. He could have just been a huge star in Japan but he knew that there was bigger money to be made in the United States so he always had that on his mind.

Was the Anthony DeMarco fight his defining moment as a boxer?

I think that’s the closest we came to seeing the complete boxer that he always was. He had to go on the defensive because he suffered a bad cut. And in order to be defensive and still throw his bombs — that was quite a performance. DeMarco was an experienced and talented fighter and Valero made him quit. I think it was probably as good as we saw him (Valero). Maybe he was even better than that. We’ll never know.

How does Valero go from a career-high win to murdering his wife and killing himself in jail just months later?

It was what they might call a ‘perfect storm.’ His family and her family both say that they could see it coming. His temper seemed to get worse. It was a mixture of drugs and the mental problems that were not being dealt with. His managers kind of hoped his problems would just go away like it was a phase. Like ‘he just needs to fight more often. We’ll get him that big fight down the road.’ Really what he needed was help. There was a story that he was going to go to a rehab clinic in Havana (Cuba), but he never made it.

That’s what surprised me most about your book is that most people who think they know the Edwin Valero story would simply classify it as your ‘live fast, die young” narrative.

It’s really about mental illness more than anything else. And how when someone needs help and doesn’t get it, terrible things can happen. I did some research on how he was showing signs of schizophrenia, although he had never been diagnosed. There are studies that show how some schizophrenics use cocaine to actually calm themselves down. Cocaine has an effect on schizophrenics where it kind of levels them out. So he may have been using a lot of cocaine just to level himself out. But the end result is that cocaine also is destructive. It was making him paranoid.

I keep seeing this duality in his life (boxer-brawler, hero-antihero, etc) and his death as well.

His death had different reactions around the world. America just treated him as this monster. ‘Good riddance to this crazy character.’ But in Venezuela, it was a tragic scene. He was very involved in the little communities, the poorer sections where he had grown up. He was buying ambulances for one of the towns. He was a sort of guy who would show up on Christmas Day with presents for all the poor kids in the neighborhood. His death was the downfall of their sports hero. So that was the most interesting thing to learn about him. And I put it all in the book.

Purchase BERSERK: The Shocking Life and Death of Edwin Valero (HERE). Don Stradley has written for The Ring, ESPN, and Ringside Seat. Follow him on twitter @DonStradley